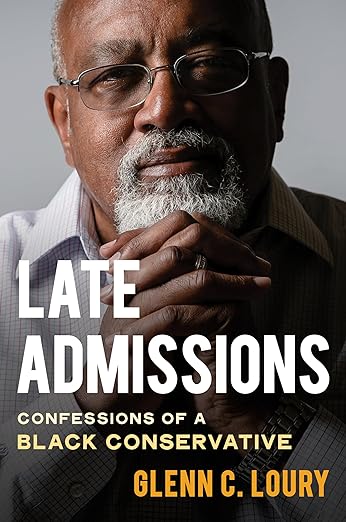

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: April 30, 2024.] Russ Roberts: Today is April 30th, 2024, and my guest is economist and author Glenn Loury. His Substack is simply Glenn Loury. This is Glenn's second appearance on EconTalk. He was here in July of 2020, talking about race and inequality. Our topic for today is his memoir, Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative. Glenn, welcome back to EconTalk. Glenn Loury: Thanks, Russ. It's very good to be with you. Russ Roberts: I want to let parents listening with children know that today's conversation may include a number of topics inappropriate for children. You may wish to listen before sharing. |

| 1:16 | Russ Roberts: This is an incredible book. As listeners know, I'm very busy. I'm not sure listeners know that I try to read every page of every book I discuss here on EconTalk. So, when I'm asked to consider a book of 448 pages, which is the length of Late Admissions, I usually just say, 'No,' right away. There's no way I can read a 448-page autobiography. But out of respect for Glenn, I picked up the book and I looked at the opening pages; and I couldn't put it down. I read every page, I think every word. It is an extraordinarily interesting book about what it means to be a human being, a man, a black man, a husband, a father, as well as an economist and social critic at the highest levels. Along with Glenn's very eventful career as an economic theorist. We get a great deal of information about his infidelities, his drug use, his arrests, his journey as an observer of race issues in America. I've never read anything quite like it. Glenn, why did you write this book with the degree of revelation you chose to share about your personal--I'd have to say--failings? Glenn Loury: Well, Russ, I thought it was time to come clean with myself, with my children. I thought there was no point in playing about such a project. The book couldn't be opposed. It couldn't be a brand-enhancing advert. It had to come from the soul. I say somewhere early in the book, in the Preface, I had to tell it all. If I didn't tell it all, nothing I said would really be credible. And I tried to explain what I mean by that. But I didn't want to be lying to myself. One of the ideas that I played with in the book is the contrast between the cover story that one tells others and one tells oneself about the most difficult and the darkest corners of one's life. The cover story and the real story. I won't go on long on this. I did go through a Christian conversion in my late 30s and early 40s, and I did go through a wrenching recovery from drug addiction. And, in that place in my life, I learned that if I didn't tell myself the truth about what I was doing, why I was doing it--how do we say in the movement? We say, 'Secrets make you sick.' If I didn't come clean with myself, I wouldn't get better. I wouldn't be able to solve the problem of self-command. I'm in my 70s, Russ. I just felt it was time to come clean. So, why play at something like this? I don't need to write a memoir. It's not as if I can't make a living just teaching and doing research and economics. The whole project would have seemed, like, opposed. There would have been something fraudulent about it if I didn't tell the truth. And so, I did. |

| 5:00 | Russ Roberts: And that metaphor--the cover story and the real story--is very haunting and very powerful; I loved it--because, the cover story is the story without all the details, and by leaving out some of the details, we allow a narrative to emerge that protects ourselves from our self. It protects ourselves from others. It protects ourselves from judgment. But, time and time again in this book, you give us both the cover story and the real story. You talk about the fuller image, more of the facts, the full color version of what was happening to you at the time, both in your head and around you--your actions, what you told yourself that was true, what you told yourself that wasn't true; and now you're looking back on it. It's a very powerful way, I think, to think about the challenge that you say of self-command. Which, you know, I'm almost 70, and I feel very similarly to you that, that project is a huge part of what it means to be a fully realized human being. It's taken you a while--it's taken me a while--but the book shows a great deal of progress without being self-congratulatory, I would say. Is that a fair assessment? Glenn Loury: It's a beautiful assessment. It really is gratifying to hear you say it. It's what I was trying to achieve. It has been said about this book--Evan Goldstein in "The Chronicle of Higher Education" said this: he said, 'Is it self-revelation or is it self-sabotage?' A good friend of mine whom I've known since grad school, Ronald Ferguson, took me aside at my son's wedding. My son Nehemiah just got married. He's in his early 30s. And, Ronnie was there and he said, 'God, I don't know if I[?] like this guy that is being revealed to me in this book.' And, I remember my response to him was, 'I'm not sure I liked him either, but I'm not that guy. I am not that guy.' And, what's the difference between me and that guy? To me, I see that guy for what he was and see myself in him, but I'm not that guy. That guy couldn't have told himself the truth about his life. So, I'm throwing myself on the mercy of the court here, a little bit. You know, I'm saying: 'Warts and all, here he is. He's struggling. He's trying to be better. He's trying to be honest. Can't you see him? Can you see him trying to be straight?' 'The guy who can tell that story in that way, maybe he's not such a bad guy after all. Maybe he's not so different from me,' I'm asking the reader to think when I lay it bare like that. You can see him in his low points, but you can also see him struggle to pull himself and stand up straight with his shoulders back. So, anyway, it is a bid to offer something to my readers that will stick to the ribs, something sturdy, something human. Russ Roberts: It sticks to the ribs, all right. We just finished the holiday of Passover here in Israel and around the world. It's still going today if you don't live in Israel. But, I finished the book sometime in the middle of the holiday, or most of it, and I had trouble not talking about it all the time. So, it definitely--and sharing it with strangers, which is a little bit weird, as opposed to talking about the holiday of Passover. But, so, I'd say it does stick to the ribs. |

| 9:41 | Russ Roberts: Talk about your childhood and that incredible--so just to preface this, at the age of 17, you fathered a child. You found yourself married with two children very shortly after that, and you grew up in a--well, I want you to talk a little bit about how you grew up, what kind of neighborhood and economic life that you had as a young man, as a boy, growing up. But shortly after that--and this part of the book is quite extraordinarily inspiring; you could make a movie out of just this part--you find yourself in graduate school at one of the most demanding programs in economics. It's a dizzying ascent from the challenges of both your childhood and then marriage at a very young age with fatherhood on you. Talk about that transition and how you coped with it mentally. It's an extraordinary part of this book. Glenn Loury: Well, I was born in 1948 on the South Side of Chicago to a close-knit family. My mother's family was very close-knit. My mother and father divorced when I was quite--four, five years old. I had one sibling, a sister. So, I was raised by a single mom--my mother, a wonderful woman, a sweet, gentle, kind, giving woman, but not the most organized, responsible, diligent parent, and had a wild streak. Her brother, Alfred, called her Go-Go. Her name was Gloria. He called her Go-Go, because she was always on the go. She and my father split up, and she remarried. That marriage didn't last very long. We moved--we moved a lot. By the time I got to the fifth grade at 10 years old, I had been enrolled in five different schools. Her sister, my Aunt Eloise [pronounced E-lo-ees'--Econlib Ed.], was just the opposite in terms of the degree of command over her life and responsible, organized living. Her sister was a matronly, ambitious, church-going woman, who owned a nice-sized house. I mean, today, it wouldn't seem much to me, but at the time, it was a mansion: six bedrooms, a beautiful living room with a piano. But, my Aunt Eloise was a woman who would not sit by idly and watch us--that is, her sister and her sister's children--be dragged around apartment to apartment. And, saw to it that a small two-bedroom unit was created upstairs and into the back of her large house. When I was 11 years old--10 or 11 years old--we moved in. And, I spent my most formative years in that house, in that little apartment. These were working-class/middle-class people. I mean, my aunt and uncle, Uncle Mooney--her husband, James A. Lee--Uncle Mooney. They called him Mooney because he had these big eyes that protruded half-moon-like. And that was his nickname, and it just stuck. He was a barber and hustler, small businessman. He'd buy and sell things. He did what he needed to do to make a living. Most of it was legal. He sold a little bit of cannabis out of the back of his barber shop. He knew the guys, the Italian guys, who would hijack trucks. So, when there was a truckload of suits that had gone missing, a half dozen of them might end up in my uncle's barber shop in the back that he'd resell. They had a dry cleaners for a while where they were operating another kind of business. So, they were business people. He didn't work for anybody. My Uncle Mooney didn't believe in working for the white man. He didn't believe in banks. He had come up in the Depression era and had watched banks go bust, and he kept his life savings stuffed into old fruit juice cans that were under a floorboard in the closet off of his bedroom. And, this was my domestic situation. |

| 15:05 | Russ Roberts: Somehow you end up at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] for graduate school at a time when MIT is arguably the best program in the country. I went to Chicago around then. I might have disagreed with you if we'd met at a conference. But, what was that like to walk the halls of MIT, to have Solow and Samuelson and other great minds as your professors, given your background? And, how did you relate to that program as a--I was going to say, as a black kid from the South Side? You weren't a kid anymore at that point, but given your upbringing? Glenn Loury: Yeah. I just turned 24 when I arrived at MIT. I was just blown away by MIT. I was intimidated at first, but I got in the classroom and I did pretty well. Paul Samuelson, yeah, Bob Solow, Peter Diamond, Franco Modigliani. Franklin Fisher. The econometrician, Stanley Fischer, the monetary theorist. Martin Weitzman, the micro theorist. Peter Timmins, the economic historian, and others. And, by the way, the Sloan School wasn't that bad either. And, there were some pretty good economists at the Sloan School, and there was a lot of work going on in operations research and queuing theory, and stochastic dynamics and things like that, that I was exposed to. I took to it. I did very well. That's for someone else to say. But I was near the top of my class of students at MIT from day one. And, I flourished. A black kid, yeah, and there weren't so many of us. MIT did have an outreach to try to bring in African-American students to their Ph.D. program. As was explained to me later--I actually didn't know it at the time--the faculty had decided that while they were going to admit 25 or so in each class. They would add--I'm not sure where the funding for this came from--an additional three admissions that they would use to identify the most promising black graduate students that they could identify in the [inaudible 00:17:36] in MIT. And, in the year that I was admitted, 1972, there were three of us African-Americans--Ronald Ferguson, who I've mentioned was one, and then there was another guy. Would I have been admitted without the affirmative action? I'd like to think so. I had an outstanding record at Northwestern, but it is MIT; and it was arguably the best department in the world, and a lot of really good applicants didn't get admitted, so I don't know. But, I got there and I did well. I made friends. I made Jewish friends, because a lot of the people in the faculty and in the student body were Jewish. I had a very close friend, Pinti Kouri, K-O-U-R-I. He's no longer living, unfortunately, a Fin, who took a liking to me and kind of almost adopted me, I'm going to say. He could see I was rough around the edges. I was an urban kid. I didn't have a lot of sophistication and about the fine arts, about what knife and fork to use when I'm at a table, about what wine to drink or whatever like that. Pinti kind of befriended me and invited me into his circle of friends, and I enjoyed that. But, it was mainly the work. It was very exciting. I was no longer required to put in eight hours a day, five or six days a week at a job. All I had to do was go to the library and find journal article and study it with my yellow pad and my pen, go to office hours, do the problem sets, and so on. And, I did. Unfortunately, my marriage to Charlene collapsed in the early years of our time at MIT. We separated and ultimately divorced. Our two kids now were in a broken home. By the time I finished my dissertation four years after arriving at MIT, Charlene and the kids were moving back to Chicago, and I was on the job market. |

| 20:02 | Russ Roberts: So, you come out of MIT: you are a world-class mathematical economist. You're an economic theorist of the highest order. You publish a series of articles in the very best economics journals, and your career, it just takes off. And, a few years after you've left MIT, you get tenure at Harvard. So, in many ways--you're 34 years old, I think, if I have that right--you're at the peak of your profession. You've achieved what many people would say is the pinnacle. But it doesn't go so well. And, you have a conversation with Thomas Schelling, one of your colleagues, and you confess your unease that you're not living up to the standards that you've set for yourself and that you fear the standards that your professors who recommended you to Harvard and your colleagues expect of you. And to your chagrin, he laughs in your face. Which is not what you were expecting. Why did he laugh? Glenn Loury: Yeah, it was definitely not what I was expecting. He said, 'You think you're the only one? This place,'--he speaks of Harvard--'is full of neurotics, hiding behind their secretaries, fearful of the dreaded question,'--this is a quote--'"What have you done for me lately?" See, we're all a bunch of neurotics around here, who can't stop looking over our shoulders, fearful that they're going to get us. They're going to get us. They're going to find out where frauds. Just relax and do your work.' That's what Tom told me. But I want to go back a minute, Russ, just to explain. My first job out of MIT, and I did do well in graduate school--Bob Solow was my thesis advisor. I wrote what I thought was a pretty good thesis. One of my papers ended up in Econometrica. That came out of that thesis. I had other papers as you're noting: the Quarterly Journal of Economics, in the Review of Economic Studies, and so forth. My first job was at Northwestern, out of MIT. So I was at Northwestern as an undergrad; four years later, I'm back as an Assistant Professor. Guess who was there with me? Roger Myerson was hired in the Mathematical Economics and Decision Sciences Program in the business school at Northwestern, the same year I was. Bengt Polstrom was hired in that same program the next year. Paul Milgrom was hired in that same program the year after. I was colleagues with all three of those guys in the late 1970s at Northwestern, before I went to Harvard. This was the dawn of mechanism design theory and incentive compatibility theory. There's a guy called Leo Hurwicz. If you don't know who he is, you should look him up, whoever is hearing me speak these words. He was working out some foundational stuff on how do you design economic institutions where there's incomplete information, taking full account of the incentive structures of the participants buying and selling options, and things like that. But, had a general theory of resource allocation under incomplete information. Roger Myerson was doing his foundational work on the theory of auctions; Paul Milgrom. Now, everyone that I've mentioned here is a Nobel honoree. Those were my peers. So, when I finally got the call from Harvard, and it was Tom Schelling calling, representing a committee that Henry Rosovsky, the fabled Dean of the faculty at Harvard University, in those years, late 1970s and early 1980s, he had put together a committee to rescue the Afro-American Studies Department at Harvard, which had fallen on hard times academically speaking, and they wanted fresh blood to invigorate the program. And, they impaneled the committee, and they wanted to hire an economist. And, they identified me. And Tom Schelling calls up and he invites me to come out there. I go out there, I'm interviewed, I give a talk; and they make me the offer. And I take the offer. And I get to Harvard. I get to Harvard as Professor of Economics and of Afro-American Studies. They said Afro-American in those years. And, I was jointly appointed. I was a full member of the department, of tenure, the first Black to be a tenured member of the Economics Department at Harvard, and a member of the small, struggling but ultimately successful Afro-American Studies program. This is before Henry Louis Gates Jr. came in and took it over. But, I was there in Afro-American Studies with a historian named Nathan Huggins and a literary scholar named Werner Sollors. And, both of those--Huggins, unfortunately is dead--are estimable figures in their field. So, Rosovsky's efforts to invigorate Afro-American studies even before Henry Louis Gates Jr. came to Harvard were successful. But, I was not successful. I was straddling these two different realms, the academic economics and the Harvard Economics Department, of course a great department. And, I can remember the first faculty meeting that I went to in the Economics Department at Harvard. I looked around the table and everybody I saw was famous. They were all great men and women--not as many women, but Claudia Goldin and I overlapped in those years. We were both young, full professors at the department. She had been at Penn and came up to Harvard roughly the same time that I did. But, any case, I was fearful that I wasn't going to be able to continue to produce the kind of work that merited this appointment that I had in economics. And I had a crisis of confidence. That's what led me to go to Tom and bare my soul, and struggled to try to find my way. The Economics Department at Harvard wasn't unkind or unwelcoming, but it also wasn't warm and fuzzy. Everybody was busy and taking care of their own business. Michael Spence, the great microeconomist and industrial organization [I.O.] specialist, took a liking to me; invited me to co-teach the graduate I.O.--introductory I.O.--course with him my first year there, which I did do. And, I guess I did okay at it. But I couldn't quite find my way. And, I panicked. I choked, as I say in the book. I fell into a psychological black hole. This is one of these cover-story and real-story things because I could have used as a cover story, 'Oh, the economics department, they're cold. They didn't make any place for me. They were unsupportive.' But, the real story is that I was so unsure of myself, so fearful of failing, that I lost my way and I couldn't find anything to work on that I thought was worthy of the [?]. I mean, I had some problems I was working on. I did publish some papers, but it was nothing like what I expected of myself. And, I was under a lot of stress and in distress. As I say in the book, I was drowning. I knew I was drowning. I didn't know how or whom to ask for help. |

| 28:23 | Russ Roberts: As an academic with a somewhat mixed record myself and as someone who put high expectations on myself as well, that cover story/real story is very poignant for me. I did some good work, but I did not do enough of the kind of work I thought I was supposed to do. Whether I was capable of it or--I don't know. But, I found myself, as I got older, turning to other ways of expressing my interest in economics. I wrote a novel that explained economic principles--wrote a few. And, I left behind much of the academic game that I wanted to be a player in, which is the game you talk a lot about in this book. The goal of publishing at the highest level, defending your intellectual work at the highest level from the reactions of the highest of your peers, both at your home institution and elsewhere. And, there is a battle going on inside one's head and one's soul at that point. And you end up becoming a rather acclaimed social critic. And, your criticism, it's not--I don't want to pigeonhole it, obviously; there's a lot of different aspects to it. You wrote about inequality, both as a technical economist but also from a much broader perspective, in your popular writing in these early years of your career. And, you become acclaimed for that. You gain fame, you gain applause, you gain audiences. And, in many ways, it's a seductive career path with a lot more noise to it. It's what Adam Smith would call the more glittery road rather than the quieter one. And, you find yourself spending more time in that world. And, at the same time, you're struggling to keep your personal life in order. And, talk about some of the challenges you faced in the evenings when you went in search of--I would say, in search of your roots. It's a fascinating aspect of the book that--you don't say it this way; I'll say it, and you can react to it. In many ways, you never leave the South Side, you carry it with you, and you are constantly trying to navigate your identity as a former resident of that part of town and a, still, Black man with this very, very ethereal academic game at the highest level. And, you struggle to reconcile those two; which, your description of that is--it runs through the book--is quite moving. Talk a little bit about that challenge and your failings, which you admit to throughout the book. Glenn Loury: Well, first, I just want to thank you for your close attention to the book. I really appreciate it. Yeah, so you said a lot there. Let me start at the beginning, cover story and[?on?] your story about failure as a theorist in the economics department, about choking, about imposter-syndrome-type stuff. And, I was drowning and I didn't know whom to ask for help. Well, my dissertation advisor, Bob Solow, came along. I had been at Harvard for a year. Everybody knew I was one of the top students in my class of 1976 coming out of MIT. I had been relatively successful at Northwestern, and I spent some time at the University of Michigan, where my second wife, Linda, who I met in graduate school after Charlene and I broke up, was working as an applied labor economist. And, I spent some time in Michigan. But I ended up at Harvard. And I'm in this joint appointment. And, the second half part of the appointment is Afro-American Studies. And, even before taking the job at Harvard, I had been thinking as a intellectual, as an economist, but as a person who is interested in the world of ideas and politics and public policy about the problems of the inner city, about the, quote-unquote, the "crisis of the Black family," about crime, and police, and prison. About low academic performance and Black underrepresentation in one way. And, this is now--gosh, time has really flown--Civil Rights Act of 1964 is less than 20 years old. The question--it's a burning question: Do the effects of historical African American exclusion wither away and attenuate in the face of opening opportunities created by the reform of the society in terms of anti-discrimination and so on? And, there's a lot of popular discussion of that question as well as academic discussion within economics, and sociology, and politics, political science, and history. There are people writing magazine articles in The Atlantic, or The New Republic, or The New York Review of Books, or whatever, who are taking one or another stand on where the country is with the, quote-unquote, the "Negro problem"--with the solution of the 'American dilemma,' as the economist Gunnar Myrdal had put it in his classic work, post-World War II study of the Negro's situation within the American political economy. And, this interested me. I was of the relatively conservative opinion that--for which there was some evidence, although there was certainly counter-argument--that the Civil Rights legislation had been enormously successful in eliminating overt racial discrimination. But that it was unclear whether that success would, in the fullness of time, lead to a situation in which socioeconomic disparities between the races would go away or would get near to zero. And in fact, I said that one of my dissertation papers--there were two papers in my thesis at MIT, and one of them ended up in Econometrica--which ain't too bad. But, the other one was published in a conference volume. It was called "A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences," which I wrote with the support of an African American woman, who was an economist in the faculty of the Sloan School of Management at MIT, named Phyllis Wallace. And, I helped her organize a conference, and I wrote a paper for that conference, which ended up as part of my dissertation. And, it put this question--the question was: Suppose you have an economy in which you have racial groups and in which you have a history of discrimination; so, one of the racial groups lags behind. Suppose you have intergenerational transfers, so that the human capital development of the young generation depends upon the resources available to the older generation, and that this works differently for the different racial groups because of segregation. So, there's social segregation, and there's intergenerational transfers. The social segregation is along racial lines. The intergenerational transfers are occurring within families. Now, parents of a generation which has been discriminated against will not do as well. And so, they'll have less resources to bestow on their kids, so their kids won't do as well. But, if there's also social segregation, that kind of intra-family dynamic will work differently for the different racial groups. And, I fashioned a mathematical model--a little discrete-time, dynamic, stochastic model--where I could show that under some circumstances, even if you got rid of all the discrimination, the incomes between the racial groups wouldn't necessarily converge. So, the anticipation that ending the discriminatory regime would lead, even in the very, very long list of runs, to group equality might be falsely grounded. It was a counter-example to the claim that laissez faire will take care of everything in the long run, even if you had a history which was racially discriminatory. So, I wanted to get that on the record for our conversation as a backdrop to what I'm about to say. So, I started thinking about: 'Well, what can be a solution to the problem of persistent racial inequality?' And I started thinking that a lot of the stuff that's going on within African American communities, that values and attitudes and norms and behavioral practices and culture were also instrumental in the perpetuation of racial inequality. Not just discrimination. And, I started thinking that the agitation--the political agitation of the Civil Rights Movement and the activists--the ones who were against police brutality and who were demanding that companies not have employment records that were roughly racially representative and so on, wouldn't really reach deeply enough to counteract the historically-inherited practices and patterns of living among African Americans that were a part of the problem. And I started, even before I got to Harvard, expressing those thoughts. Expressing them privately to friends and associates, expressing them casually to colleagues, and expressing them in my writing of little essays and talks that I would give in which I try to, in a heterodox way, in a critical way, address the problem of persisting racial inequality. Now, this is relevant to your asking me about my own life, because some of the motivation for thinking in terms of African American culture and in terms of family structure and behaviors came out of my own experience on the South Side of Chicago about what I saw, and what I knew, and about how people were living. Early in this book, I reveal the fact that my sister and I had different fathers, even though my sister is just one year younger--she's dead now; my late sister Leonette[?] is just one year younger than me. And, my mother had an extramarital affair and ended up becoming pregnant with another man, not her husband's baby, who was my sister. I reveal that my uncle--my mother's brother, Alfred, the one who nicknamed her Go-Go--would in the fullness of time, fathered 22 children by four different women and lived a Mormon-esque--forgive me if I offend anybody--but as a polygamist. My aunt was a very respectable woman. She was Chairman--Chairwoman--of the SORELIT Guild--S-O-R-E-L-I-T--SORELIT, Social, Religious, and Literary Guild, of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church on the South Side of Chicago. These women held fashion shows, and they organized voluntary charitable events, and they--teas--and high societies where Negro Chicago kind of stuff. But, my mother's other brother, Atler[?], a notorious womanizer, had managed to seduce half of that committee of church women at one time or another. And this was a notorious, commonly-known thing that was going on around me. I lived in a pretty decent neighborhood--my aunt's neighborhood on the South Side, 7329 South Michigan Avenue, Park Manor--where there were low-density housing, green lawns in front, and so on. But, the kid down the block from me died of a heroin overdose at 18. Another kid who I was friendly with in the Little Leagues bled out on his mother's basement floor from a gunshot wound that went untended when he was fooling around with a gun with his friends. Another kid who was a bully, who made my life difficult when I was in seventh and eighth grade, ended up with a life sentence for shooting a cop while trying to get away from a robbery of a currency exchange. There was--not a stone's throw away, there were neighborhoods where there were streetwalkers walking the streets, where there were open air drug sales going on, where the gangs were ruling the nest. This was a world that I was more than casually acquainted with. It was, in a way, my world. Yeah, I was precocious. Yeah, I was bright. Yes, I was relatively well-off because my aunt and uncle were relatively prosperous, all things considered. I never knew a day when I was hungry. I didn't go to bed fearful, hearing gunshots echoing in the surrounding neighborhood. But, the housing projects where one of my uncle's families were raising their seven children, were places that I visited frequently. That world--the ghetto--that was a part of my life. That was a part of my world. So, I, in so many words, invite the reader of this book to consider this juxtaposition between my own life--as you say, rarefied specialist in a technical field at a high level--but with an interest in the problem of persisting racial disparity. On the one hand, my personal life and the social milieu from which I emerged--a milieu, a world, a way of being in the world, which I took to be authentically Black. I always had an issue with the rarefied--socially rarefied--upper-class, saditty, full-sophisticated Black bourgeoisie. I remember reading E. Franklin Frazier's book, Black Bourgeoisie, of that title in which he satirizes and criticizes the world of high Black society of the 1940s and 1950s. And, I thought of myself as earthier, as more grounded--frankly, as blacker than a lot of Black people. And, part of that blackness had to do with my ability to negotiate my way around the grittiest neighborhoods of the inner city and to be able to hold my own there. Being able to talk, being able to go into a club and walk out with somebody on your arm. Being able to walk the walk and talk the talk in the vernacular and in the rhythm that was characteristic of that social location. I thought of that as blackness in some essential way. I'm not defending that thought. I , with decades of retrospect, I can see the deep problems with that kind of thinking. But that is the cast of mind that I brought with me to Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1982 when I took up the position at Harvard. So, soon enough, I find myself, as you were alluding--pardon this long prelude, but I just wanted to set the stage--I find myself seeking a similar kind of social experience in the inner city neighborhoods of Boston, in Mattapan and Dorchester and Roxbury; Black Boston, Dudley Station, Washington Street, Tremont Street, Tremont Avenue, what is it? Tremont Street, I think it is. Blue Hill Avenue. I found myself going and hanging out. I had friends. I made friends. I had thoughts. I enjoyed cannabis from my late adolescence as a part of my upbringing in Chicago and my social life, and, you know, I could find it there. I enjoyed the excitement of going into a bar and taking a seat somewhere, having a drink, watching who is coming in and out and seeing what the action might be, and maybe picking somebody up and having a few hours of "illicit fun," quote-unquote, and coming back to tell the tale. There were hustlers whom I befriended. There was a guy--wonderful guy, actually--named Eddie, wore a comped hairdo [slicked-back hairdo--Econlib Ed.]. He was a vendor who sold trinkets from a tabletop without a license, but the cops left him alone. He had a little portable radio blaring music out. He'd stand near the busy byway, going to the T station, the transport hub, with a lot of foot traffic. And he played chess. He played five-minute chess for a buck a game. Anybody, he would take on all comers. He was not half bad, but he wasn't as good as me. And, you know, I'd hang out with him down there, and hang out with him and experience a lot of the life, the vitality, the earthiness, the riskiness, the thrill of being in that social location. And, it ended up getting the better of me. |

| 49:34 | Russ Roberts: This is while you're married, while you're a professor at Harvard-- Russ Roberts: You're leading--a good chunk of the book is about this double life of respectable Harvard faculty member teaching by day, and at night, the hustler, frequenter of bars, smoker of weed; but eventually user of cocaine, and it comes crashing down. What goes wrong for you? Glenn Loury: Well, a couple of things go wrong. One of them is I take a mistress and it--I rent an apartment and I'm keeping her there. She's a 23-year-old graduate of Smith College. It's a long story. You can read the book about how it is that we need and hook up, but in any case-- Russ Roberts: You're 38 at the time, right? Glenn Loury: Yeah, that's right. I'm in my late thirties. She's in her early twenties. And we get into a fight, and the fight gets very raucous. I throw her out of an apartment. She's taken to a shelter. She accuses me of having assaulted her. I didn't assault her--or, I did, depending on your definition of assault. I put hand on her to push her out of a door. I didn't hurt her. I didn't think that I had hurt her. But, when I'm arraigned, she shows up in a neck brace and with a claim that I dragged her down the stairs. And I'm charged, and I have to face those charges. This becomes public. It happens at a time when I'm--on my public, intellectual side--up for a position in the Reagan Administration. I befriend Bill Crystal--William Crystal, the still-active journalist and political operative Republican. He's close to William Bennett, who was the Secretary of Education in Ronald Reagan's Second Administration. And, late in the second term of Ronald Reagan, they invite me to take the position of Undersecretary--Second in command in the Department of Education. I accept that invitation. And, I'm going to be nominated for that position. And then, this scandal breaks. I withdraw from the position. I retreat to my wife who is stuck with me, notwithstanding the outrageous abuse of our marriage, which my now-public affair reflects. Linda stayed with me. And I'm forlorn. I'm depressed. I've moved from the Economics Department at Harvard to the Kennedy School of Government. I ended up taking Tom Schelling's offer to move my chair--my faculty appointment--out of the faculty of Arts and Sciences and into the faculty of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. It's the final resolution of the dilemma that I posed for myself by choking as an economic theorist in the economics department when I first got to Harvard. I move over to the Kennedy School, and I'm at the Kennedy School when all this happens. So, I'm kind of in the doghouse. I'm depressed. And I'm finding solace, if that's what you want to call it, in this double life, which does lead in the fullness of time to encountering of free-basing cocaine, crack cocaine, which I take to and become addicted to and become consumed by, and ended up getting caught and arrested again, the second time within a calendar year, now in possession of a controlled substance, crack cocaine. And, it would appear that my life is spiraling out of control. My wife, Linda doesn't know what to say or what to do. She is distraught beyond any consolation. But she hangs in there. I end up in a treatment program, which as--an outpatient, and I blow it off and I relapse, and I keep using. I end up in an inpatient program, McLean Psychiatric Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, which has a residential drug therapy program, which I enroll in. And, I spent five or six weeks there. Come out, and quickly relapse again and go back to using crack cocaine and have to go back into the inpatient program for the remaining of my 60 days of insurance coverage for paying for hospitalization. And do stop using. Take up residence at a halfway house in Irish Boston, run by a grizzled old veteran of the recovery program of alcoholics in Narcotics Anonymous. I live in that halfway house for five months. And, during the time that I'm there--just before I go in, actually--my wife, Linda, becomes pregnant with our first child, Glenn II, who is in his mid-thirties now. I come out at Thanksgiving of 1988. Glenn is born January of 1989. I'm drug free. Harvard has stuck by me. The Kennedy School people--Tom Shelling has been in my corner the whole way, would come to visit me every week while I was hospitalized and so on. I find religion as a part of my recovery process. I've become a born-again Christian. I'm fervent about it, and absolutely sincere in my belief that my life has been restored, that Christ has lifted me out of the gutter and into a dignified way of living. That he has blessed me with a woman who has, beyond any justification, blessed me with a family, a young family. I pull myself upright and get back to my job at the Kennedy School. But, yeah: Those years, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, yeah, I'm living a double life. I'm a professor by day and inner-city bad boy by night. It practically destroys me. But I make my way through it. |

| 57:03 | Russ Roberts: In many ways, your book is a story of extraordinary resilience. And again, the honesty of it and the details which we're not covering here, but they are really, really quite thought-provoking. But, there's a backstory I want to get you to talk about, which is--and we'll talk a little bit more about your ideological or political positions. Coming out of graduate school, you mention you'd written a piece, a paper on the persistence of inequality in the face of even the removal of overt discrimination, the challenges that the Black community has on its own. And, your book was originally--I think, one of your original titles was The Enemy Within, and that's a play on words. The Enemy Within was, within the Black community, that despite the Civil Rights Act and efforts of Affirmative Action, there would still remain a cultural challenge that the Black community had to take its own responsibility for. And, at the same time, the Enemy Within is the demons that are haunting you. That are your imperfect behavior. Which you write about. So, here's the arc of Glenn Loury's policy prescriptions. He starts off talking about the enemy within, saying the Black community, it's not enough to say that there's racism in America. We have to bear some responsibility for our own actions. You then--I'm not going to get the dates right--but at some point, so you're called a conservative. You are talking to Bill Kristol. You are going to work--potentially, you were going to work in the Reagan Administration. And many people on the Left call you a traitor to your people. But, at some point, the Conservative Movement--and you highlight Charles Murray's book and the Thernstroms' book, and we won't go into it here--but your reaction to that conservative thought makes you uncomfortable with where you've landed. And, you become much more focused on the role of incarceration, the failures of both government and American society to help Blacks lift themselves up. And now we come to something like the present: You've come full circle. You self-identify as some kind of conservative, not the kind that--we won't even try to describe what it means to be a conservative in America in 2024. I even have trouble with that myself. But, the point I want to make, which you write about quite eloquently and poignantly, is that in your first round as a, quote, "conservative," you're railing publicly with indignation about the self-failures of the Black community; but you're living a life that is part of that failure. You reveal your imperfection as a husband. You reveal your imperfection as a father. And, at one point, Richard John Neuhaus says to you: 'You're a hypocrite.' He doesn't say it literally, but that's the sin he's laying at your door. You're leading an inconsistent life. You are demanding a level of conduct for the Black community that you cannot sustain, yourself. And, your answer, which is very reasonable, is: 'Well, what does my personal behavior have to do with whether my views are correct?' And yet, this struggle internally, between your social critique of American society--both from Left and the Right--is constantly struggling with your own personal behavior. And, I think it's part of your brokenness is your inability to reconcile those--at least certainly in the years that we're talking about, when you were at the beginning of your role as a conservative critic. Reflect on that. Glenn Loury: Well, that was very well said on your part. That's right, I was calling the book The Enemy Within. That was my title, and that was my idea--the idea that you just encapsulated, which was there was an enemy within Glenn Loury. There was an enemy within the Black community. And I wanted to play on the relationships between those things. And, one dimension of that is the hypocrisy point that you call attention to by reciting what Father Richard John Neuhaus had to say to me: You're either a moral leader or you're not; and you have a responsibility to live decently if you're going to exhort your people to live decently. In that conversation, I called to his attention the fact that Martin Luther King Jr. had not been faithful to his wife, and nobody said that that made him any less of a figure of national importance for moral leadership in the country. And that made him very angry. And he said, 'King's inconsistency in that regard was a terrible flaw that hurt the Movement.' And, he didn't know what he was talking about, because he marched with Martin Luther King in the 1960s--father, then pastor--he was a Lutheran and converted, reverted, depending on how you look at it, to Catholicism later in his life. So, and, you started this interview, Russ, by asking me why was I so candid and honest? And, as you remind me of The Enemy Within and the double meaning of that phrase, it stimulates me to think that that kind of sense that you can't be a moral leader--you can't tell people how to live. I mean, I want to say today, I want to say we, Black people, especially those of us who are at the margins of society, have a responsibility to take control of our lives and raise our children, to build up our communities, to develop our social capital, to affirm the ways of living that are most consistent with realizing the potential of opportunity in this society. And, I feel like I can't lie about my own life and have that be my message at the same time. So, yeah, I mean, again, there was a lot packed into your question. I was a conservative in the Reagan era. I became a culturally conservative religious Christian in the period in my life when, thank God, I was able to put things back together. When Linda and I started our family, we had two sons--ultimately my late wife--Linda Datcher Loury, Professor of Economics at Tufts University, colleague of mine from graduate school days, mother of Glenn the Second [II], and Nehemiah. And became more culturally conservative. I befriended Charles Colson, the notorious Nixon era figure who became a Christian evangelist and activist, founded the Prison Fellowship Ministries, Charles Colson did, which I served on the board of for years, at his invitation. We were broken men and women. Some of us knew the inside of a prison cell. I never went to jail, but I had public humiliation and legal problems, who were now devoted to serving the families and individuals who found themselves on the wrong side of the law in a spirit of Christian love. This was Colson's Christian Fellowship Ministries, and I was a part of that. So, I was conservative. I listened to the Christian radio. I went to Colorado Springs to focus on the family's headquarters and gave my testimony--that is my account of how I had been brought from literal death. I mean--I was robbed twice at gunpoint in the streets of Boston out there at 1:00 AM in the morning trying to buy drugs or whatever. I could have easily lost my life there, back to life. But, I found it uncomfortable in a way, being the Black mascot of the neoconservative/conservative social policy world. And there were these books--Murray's and Herrnstein's, The Bell Curve, Abigail and Stephen Thernstrom's America in Black and White, Dinesh D'Souza, The End of Racism, those were promoted by the American Enterprise Institute [AEI], where I was an advisor to Christopher DeMuth, who was President of the AEI in those years, by the Manhattan Institute, where I am a Fellow, even to this day, in New York City, relatively conservative think tanks. I was a part of that world. I wrote in Commentary, I wrote in First Things, I wrote in the Public Interest. I wrote in The New Republic. And I wrote from a heterodox, relatively conservative point of view. But, I wasn't comfortable. I came not to be fully comfortable there. I came not to be satisfied with, as I put it in a long review that I wrote of Abigail and Stephen Thernstrom's book, which was published in 1997 in The Atlantic. I said, 'It's just not good enough to be right about liberals being wrong.' Don't you care about these people? The reason that I became a neoconservative, I said this to Norman Podhoretz at Harvard on the occasion of celebrating the 50th anniversary of Commentary Magazine over which he was a publisher and editor-in-chief, and he said, 'We're all conservatives now. There are no more neoconservatives.' And, I objected. I said, 'Look: Neoconservatives are liberals who've been loved by reality,'--that was a famous definition of the neocons. But, we still want solutions. It's just that we want to stay in touch with reality. We don't want to write these people off. We are not prepared to just give up the search for how to solve social problems. These are our people in these ghettos. We have to help them somehow. That's not a idle or a fanciful or idealistic thought. That's decency. And, I felt that conservatives were quite happy to write off my people. I speak now of struggling African-Americans, in urban American. So, I found myself breaking ranks a little bit with the conservatives and losing friends, like Abigail and Steven Thernstrom. And trying to go home again, which is another one of my themes in the book-- trying to mend the fences that I had broken with other Blacks through my apostasy. But, you're right: I mean, I suppose this interview cannot go on forever, the one that we're having right now. I should try to bring things to a close. I took up, like, the state, against over-incarceration and especially its racial aspects. In 2007, I was invited to give the Tanner Lectures in Human Values at Stanford by the committee out there, and I went out and I gave a couple of lectures on race incarceration and American values. And I began, I don't know, 5-, 6-, 7-year period where that was pretty much all I wanted to talk about: how many black men, how many people are in prison, how Draconian, how 'lock them up and throw away the key'-politics was ruling in many places; how the hope of rehabilitation had been abandoned, nothing works; and how devastating the effects of incarceration were on the communities--the inner-city, low-income communities, like the ones that I knew in Chicago from the high incidence of institutionalization of the prime-age male population there. And, I was anti-incarceration with a vengeance. Collaborated with the sociologist Bruce Western on launching studies at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and at the National Academy of Sciences. On incarceration, we produced work including a nice volume from the National Research Council on causes and consequences of high rates of incarceration. And I was an anti-incarceration liberal for a while. But, the era of Black Lives Matter, the Trayvon Martin--I think that's 2012--Michael Brown, I think that's 2015; culminating in George Floyd--the era of Black Lives Matter, of anti-racism in the person of the likes of the Ibram X. Kendi's How to Be an Antiracist or the Robin DiAngelos of the world really soured me on liberal anti-racism. And, I've tried to articulate the reasons why in some of my more recent stuff. Russ Roberts: And you often talk with John McWhorter on these issues with great eloquence and interesting observations. |

| 1:12:13 | Russ Roberts: I just want to share a thought that I had reading your book. One might conclude from your journey in the policy space that you are a contrarian more than a, quote, "conservative"--that you are constantly pushing back against the received wisdom of the day, whatever it is. And, when you were, quote, "a conservative," you were pushing back against the people who continue to embrace the Civil Rights Act and that approach. Then when that went too far in your view, you pushed back against, as you say, the incarceration phenomenon--the magnitude of it. And then, in the current world of political correctness or woke, DEI [Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion], etc., you've pushed back against that. And, I think I understand. I know many economists who have this trait that they push back against the wisdom of the day. But I'm going to--with something often counterintuitive. But I'm going to give you a different description and see if you agree. I think you're nuanced. And, I think nuance is difficult. Nuance doesn't sell. You are a serious academic, in that I think you like to at least think that you're pursuing the truth. And when people pursue it carelessly, you judge them accordingly. And that gets you in trouble. And, contrarianism is a mindless opposition to the fads of the day. Not the worst perspective to take. But I think it sells you short. I think you are more of a nuanced thinker who is reacting to the simplicity of the narratives of the day, and inevitably, that makes you very unpopular with those folks who are selling a less nuanced but often popular narrative. Do you think that's a accurate description of who you are, Glenn Loury, in 2024? Glenn Loury: Yes, I do. And I appreciate it, because I hadn't quite ever put it to myself that way. Another person who is going to be reviewing this book said to me what you just said, contrarian, said, 'You're a guy who, if you're in a club, you're going to be on the outer fringes of whoever it is that's in that club because you like to be critical.' But I much prefer the formulation that you offer, which is I have extremely high standards of rigor in my thinking, for my thinking or any movement or program at which I would be a part[?]. And, I think the tendency to create slogans and to build on simplistic stick-figure characterizations that don't make distinctions and don't appreciate subtleties, that my abhorrence of that small way of thinking and then the building of this kind of, you know, us and them, we who are the right-thinking folk of our ilk. I mean, let me give an example. I think mass incarceration--I was a crusader from 2006, 2007 when I gave those lectures at Stanford right up into the teens. Michelle Alexander, publishes--this is the writer who had been at the Ohio State Law School when she published a best-selling book called The New Jim Crow about mass incarceration, which basically says the present day use of prisons and policing to control black populations is but the modern day extension of a mechanism of domination over black people that goes back to slavery--it's the new Jim Crow--is woefully simplistic, and lacks nuance and subtlety. I mean, for example, has nothing to say about violence--about black on black predation, about what is revealed about the incomplete development of the human potential of the young men, mostly, who are engaged in the kinds of activities that end up with them being incarcerated in the first place. Of course, there is racism in the society. Yes, you can find police brutality and you can find laws that are unequally enforced, and drug laws and so on that are disproportionately impacting on blacks. But, you can't tell me that the failures manifested by the criminal activities of these young men--failures of the development of their own social maturity and ability to perform as citizens who are not a threat to their neighbors--is an extension of slavery. That's a slogan. That's waving a banner. Calling everybody to the arms under the name of some crusade. I could say the same thing about Black Lives Matter. I could say the same thing about these ambulance-chasing attorneys and demagogues who will take every incident of a police encounter with a young black person as if it were a characterization of the nature of social life along racial lines in the 21st century, in this great country. So, no, I can't put up with that. And on the other side, I'll say the people who say they don't like affirmative action--okay, I can see that there are problems with affirmative action. They think we should be a color-blind society. Well, sure. We can be a color-blind society. The Constitution is color-blind. The Supreme Court just handed down its decision--which I don't take issue with in the Students for Fair Admissions case last summer. But the role that race plays in the shaping of personality and in the channeling of opportunity can't be ignored. If we just settle on color-blindness, go like that, say we're done with it, let the chips fall where they may, ignoring the history that has brought us here, that seems to me to be overly simplistic, as well. Anyway, there's no time to give a full development of these ideas, but I want to affirm your characterization of my being heterodox within whatever the political frame is as a reflection of my embrace of nuance and subtlety in my social analysis. |

| 1:20:32 | Russ Roberts: Well, you could have called the political parts of your book, what is, to some extent, the motto of this program: It's complicated. And I think if you're frequently making that pronouncement, you make some enemies and you reduce your ability to make some friends you might otherwise have had. And your book talks about this all the time, and it's a really thoughtful conversation within the book about the temptations to please people around us. And it's a fascinating thing. I want to close with a personal question and then give you an opportunity to reflect on this personal issue. There's a lot of anger in your book, self-righteous anger when you're on the stage talking about something that one should be angry about--say, incarceration or the way we're treated--we treat--people who have very tough times in life, all kinds of things. Anger runs through the book, especially in your younger years. And then you say the following, which is quite eloquent--you say, quote: I fought the enemy within, but in truth, he was no intruder, no stranger. I cannot disavow his actions any more than I would deny my own because his actions are my actions. I am that enemy within. Closequote. And, I'm struck after finishing your book and talking to you today that there's a placid contentment to you and your life that was not there when you were younger; that, while no person fully controls oneself--to use the phrase that I've heard Jordan Peterson use--'We human beings are not masters of our own house.' This is a eternal human challenge. It's the challenge of growing up. It's the challenge of being a fully flourishing adult in a very hard world. And I'm curious, those two dimensions--the anger and the lack of self-control that you illustrate so powerfully and sadly, often, in your recounting of your life--does that capture where you're at? Are you less angry? Are you more placid? Do you have more self-control? Glenn Loury: Like to think so. I remarried in 2017 after my wife, Linda Loury--the economist who stuck with me through thick and thin, the mother of Glenn and Nehemiah--passed away from breast cancer. She died in 2011. I remarried in 2017 to a wonderful woman from Texas. Her name is LaJuan. I speak about our relationship in the book. And, we don't have the same politics. We don't have the same background exactly. Hers was less secure economically and supportive than mine. She grew up in the same part of Houston, Texas that George Floyd--the infamous George Floyd from Minneapolis--encountered with their children grew up, and her brother. My wife's brother--my brother-in-law--knew George Floyd as a contemporary. So, she's from the rough side of the tracks. She's an autodidact. She's a fervent advocate of socialism, and I'm a neoliberal economist. I think markets do a pretty good job of solving the problem of resource allocation. And, I'm suspicious about programs. I'm trying to answer your question. You're asking me: Am I at peace with myself and have I dealt with the anger? I think I'm getting there. But I want to tell a story. The story is: We're driving down University Avenue in Palo Alto, coming to Stanford from Highway 101, my wife, LaJuan, and I. And, it's tree-lined and everything is green and beautiful; and she says something like, 'You see? Rich people have trees and they have open spaces. Poor people have to live a pod on top of each other in tenements. It's not fair.' And, I say something--you say, you were trained in Chicago--I say something like, 'If I told every poor person in a tenement that they could have the capital value of turning their neighborhood into trees, what do you think they would do with the money? They wouldn't spend it on trees. That's for damn sure.' So, you know, we're[?] like this. We're[?] like this. Anybody who has access to the archives of my podcast, The Glenn Show, will find a debate between me and the Marxist economist, Richard Wolff, moderated by my wife, LaJuan Loury. That only happened because she kept touting Richard Wolff to me, and I kept saying, 'The Marxists have their heads up their butts. They have nothing useful to say about anything.' So--and there are many other issues besides that I could go into, but I won't, in which our predilections are in opposite directions. But we love one another. I do not have to win the argument with her. It's okay to disagree. I can change the subject or bite my tongue if necessary in order not to have a wonderful evening with a nice dinner and a bottle of wine turn into--with my jaws tied and nobody's saying anything to each other. I don't have to win the argument. I wasn't always like that. There's a point in the book where I say about my crusade against incarceration when I'm giving these speeches as I gave many dozens--on five continents, practically--in Australia and Europe, in Africa, in Asia, where I was railing against the American carceral state, I say: those speeches were fueled by anger, and the facts weren't what they were. They're enough to get mad about; but I liked the way the anger made me feel. I liked the feeling. And, I can see that for the destructive force that it can be. As I say in the book, the game never ends. And this metaphor of the game--the strategic encounter between decision-makers, sometimes within the same person--who have, to some degree, conflicting objectives and behave in ways that are mutually influencing, that's a central theme for me. And I take that theme within. I mean, in this I follow Tom Schelling's The Struggle for Self-Command. He wrote books and essays about this problem of self-management and about the role that pre-commitment can play and this kind of stuff. But, not to go too far afield, I see that as an eternal struggle. As I say in the book, unless you intervene with some Deus ex machina--unless you fall into the game, the power of Christ that transcends human foibles and that you kind of put your faith in--and I'm unable to do that today. We're just on our own here. Got to make the best of it that we can, one day at a time. The game never ends. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Glenn Loury. Glenn, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Glenn Loury: Great pleasure, Russ. Thanks for reading my book. |

Economist and social critic Glenn Loury talks about his memoir, Late Admissions, with EconTalk's Russ Roberts. In a wide-ranging and blunt conversation, Loury discusses his childhood, his at-times brilliant academic work, his roller-coaster ideological journey, and his personal flaws as a drug addict and imperfect husband. This is a rich conversation about academic life, race in America, and the challenges of self-control.

Economist and social critic Glenn Loury talks about his memoir, Late Admissions, with EconTalk's Russ Roberts. In a wide-ranging and blunt conversation, Loury discusses his childhood, his at-times brilliant academic work, his roller-coaster ideological journey, and his personal flaws as a drug addict and imperfect husband. This is a rich conversation about academic life, race in America, and the challenges of self-control.

READER COMMENTS

Jason Scheppers

May 13 2024 at 9:04am

Thank you, Glenn Lowry. I always doubted your authenticity about previous discussions your discussion of your past drug use. This interview shows great inner understanding of your path. I thank you for sharing. It helps me understand your points and I am deeply grateful. I still some different opinions, but I think this can mean a great deal to solving racial problems in the United States.

Reid Berman

May 13 2024 at 1:13pm

Although I’m an avid listener of EconTalk, I have mixed feelings about many of the perspectives shared by Russ and his guests. However, I found the Glenn Loury episode to be one of the best podcasts I’ve ever heard. Despite my previous disagreements with many of Professor Loury’s opinions, I was deeply moved by his honesty. This has inspired me to revisit his past writings in the context of his life story. Thank you, Russ Roberts and Glenn Loury, for an exceptional podcast.

William Baldwin

May 13 2024 at 5:19pm

Glenn Loury’s interview, besides very interesting, lifted a great personal burden. In my 70’s now, my youthful behavior troubled me, even though, as I told my dad: “Nobody was jailed or hospitalized.”

Dr. Loury a great man, confirmed to me that I (we) were probably normal.

Larry Phillips

May 14 2024 at 12:44pm

I was moved by Glenn Loury’s courage, honesty, and desire to understand himself and the social world he studies and writes about. I look forward to reading his autobiography.

Ron Richmeier

May 14 2024 at 8:03pm

Mr Loury personifies Wisdom in my view. The clarity in which he articulates the folly found in dogmatic prescriptions for societies ills is refreshing for what I hope is the thoughtful centrists in our society. In a time when click bait slogans define our discourse, Mr Lowry and Mr Roberts remind us that it’s complicated., we know little and we can tell others what to know even less. Mind our own affairs, be generous in our patience, give and expect respect in our discourse. Thank you for your honesty, introspection and sincerity. Thank you Mr Roberts for a singularly thoughtful forum.

Monique

May 15 2024 at 8:45am

Wow. As a South African, I am deeply moved by this podcast (as was my husband who encouraged me to listen to it). I will not add my own perspective – as a ‘white’ South African (a label I dislike deeply), we tend to avoid speaking on these topics (especially online) as our intentions can so easily be mis-interpreted.

I will say that your voice is so deeply valuable in this space. I do not think your lived experience dilutes that. On the contrary – I think that is what was so precious about Nelson Mandela. Despite his experience (which earned him credibility capital in some circles), he was able to engage deeply and not in a reactionary way. I also want to link this to a previous Econtalk podcast (supercommunicators) – it feels like you are engaging in conversation rather than debate, by being real. I salute you.

Brent Wheeler

May 17 2024 at 5:35am

Thank you Glenn. A staggering story which I found very insightful. Russ your wisdom and intelligent guidance through this story – which I found tough in many ways – was really helpful.

Mitch Conover

May 25 2024 at 8:57am

I have been listening to Econ Talk for over a decade. This is my favorite Econ Talk episode, tied, for different reasons, with Russ being interviewed by Mike Munger for his book Wild Problems. Thank you Glenn for your honesty, thoughtfulness, and instructive self-awareness. Being of a similar age, I appreciated the reflections on your life and your philosophical and personal journey.

Russ let Glenn tell his story uninterrupted and I think nailed it when, at the end, Russ suggested Glenn was not a contrarian but nuanced. I thought this was an excellent tribute to Glenn, and perhaps appreciated by many Econ Talk listeners who are dismayed that the fringes of US politics garner so much attention. Thank you Glenn and Russ for all you do.

Comments are closed.